I am a huge lover of the Victorian period in literature and art, and also of the periods preceding it, the romantic and neoclassical. However times changed and however different these periods were from each other, they were more like each other than what was to follow with modernism, existentialism, postmodernism... the century of flappers and prohibition, world wars and the Great Depression; and I for one like the old better.

Too easily I could be drawn into a fifteen page paper rather than a brief blog post on some of my favorite topics, so I will confine myself to one particular point in the commentary I was reading: female sexuality. Now I have heard the Victorians reproved darkly for every sexual aberration under the sun... which is odd for we live in the days of gruesome "liberation" and nothing is too libertine for the insatiable palate of modern lusts.

In this particular article the author was writing bitterly about women and their place in Victorian society, and she put several points which I think are widespread and deserve to be more carefully reconsidered. One is that Victorians loved pictures of women being punished for sensuality or loose conduct, and that this pointed to that society's prejudicial tendencies with regards to women. Now this assertion was made as part of a commentary on a few Victorian-era paintings of women doing penance and presumably for sins of a sensual nature.

But such art criticism has its flaws of reasoning. Suppose there exists a strong stereotype about a particular period or group of people, as there does concerning the Victorians and sexuality. Now then, suppose you take a painting, or choose three paintings loosely similar in subject, and interpret the feelings or thoughts of said period on the paintings through the lens of your stereotype. In other words, you immediately imagine what the Victorians would have said or done according to how you already picture the Victorians. But this cannot then become an argument for the stereotype! It would be circular reasoning. Victorians condemned women's sexuality; I see these paintings which can be interpreted through that lens; therefore these paintings prove that Victorians condemned women's sexuality? Nonsense. It doesn't mean your conclusion is wrong; it simply means you haven't demonstrated it adequately, one way or the other. There are other possible ideas which the Victorians might have entertained when viewing these paintings, and one conjecture is as good as another without further evidence. Except that, as with all stereotypes, the case in point is most likely to present itself to the contemporary mind most easily in terms of the existing stereotype rather than any other possibilities, however reasonable.

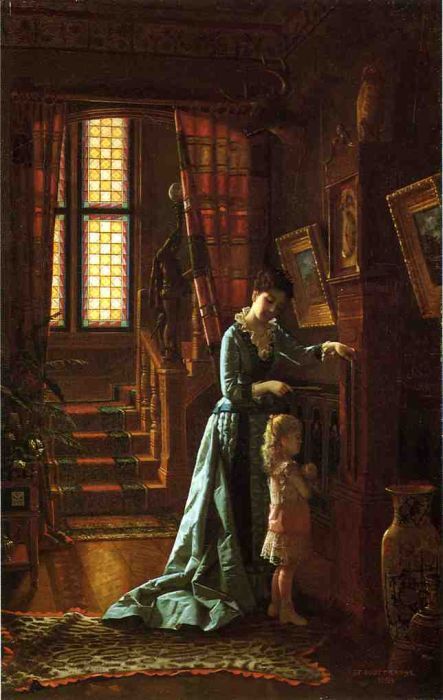

My second point is to do with the author's assertion that Victorians obviously condemned "women having too much fun." This gets rather tangled with my next thought, because the author did not distinguish between monogamous sexuality and sexuality altogether. All the portraits she alluded to were to do with women outside the bounds of an exclusive marital relationship, and by the "fun" being "too much," she meant the multiplicity or type of the women's partners. By contrast, however, the Victorians were also fond (and judging by quantity, fonder by far) of depictions of domestic bliss: mothers by the hearth with a host of happy children at their knees, fathers arriving cheerfully home from work and enthusiastically greeted, happily married couples... whether or not these depictions were a reality, they were evidently a cherished ideal. This ideal very much involves the sexuality of women, even though it is not centrally focused on it.

The Roman Venus was not exclusively the goddess of erotic love but also of motherhood and to some extent therefore the home. Many cultures and time periods have clearly tied portrayals of female fertility with motherhood. The depiction of happy mothers with children, particularly prior to contemporary means of contraception, was an acceptance of and endorsement of appropriate sexuality... in the case of the Victorians, a Christianized Western culture, that appropriate sexuality was found only within the context of a single loving marriage.

That their sexuality is not the focus of such paintings is not demeaning toward femininity. On the contrary, the author in question has pointed out the more plain and public sexuality in the "bad girl" portrayals she was criticizing... that a woman's sexuality should be focal rather than one aspect among many of the personhood a woman has, indicates smallness and prejudice. To dwell on the sexuality of the "fallen woman" is to suggest that this is the aspect of her character that she herself or someone else has made most prominent and all-important. So then one cannot be looking for positive portrayals of female sexuality solely in an erotic context. To see the happy family is to see a happy sexuality in the background, a fine harmony but too delicate for the melody... the Victorians ought sometimes simply to be accused of being private rather than prejudiced.

|

| De Scott Evans, Grandfather's Clock, tumblr.com |

|

| Sir Edwin Landseer, rossettiarchive.org |

| |||

| De Scott Evans, Winter Evening at Lawnfield and victorian valentine, goldenagepaintings.blogspot.com |

I agree. There is no doubt there was a double standard in those days, with men allowed to get away with all kinds of sexual sins and having a great many more rights than women as far as the law was concerned. But that doesn't mean that women should have been encouraged to engage in those same sins, or that it made it ok for women to be promiscuous.

ReplyDelete"The Tenant of Wildfell Hall" by Anne Brontë is an excellent book that deals with this subject. The heroine is a woman who flees with her little boy from an immoral and abusive husband. Because of the laws in England during the early 1800s, she would have been considered a criminal for doing so. However, she does not remarry and does not become romantically involved with her kind-hearted and eligible neighbor, and when her husband becomes fatally ill from his debaucheries, she returns home to nurse him until he dies. Only then does she remarry. While it shows how women of that era were often oppressed and unfairly treated in marriage, and they were deceived into marrying men who were allowed by society to commit all kinds of transgressions against God and man simply because they were men, it also advocates mature, moral responses on the part of the women. I'm more inclined to listen to the opinion of an authoress of that era than a whiny feminist of this one. Sorry. :D